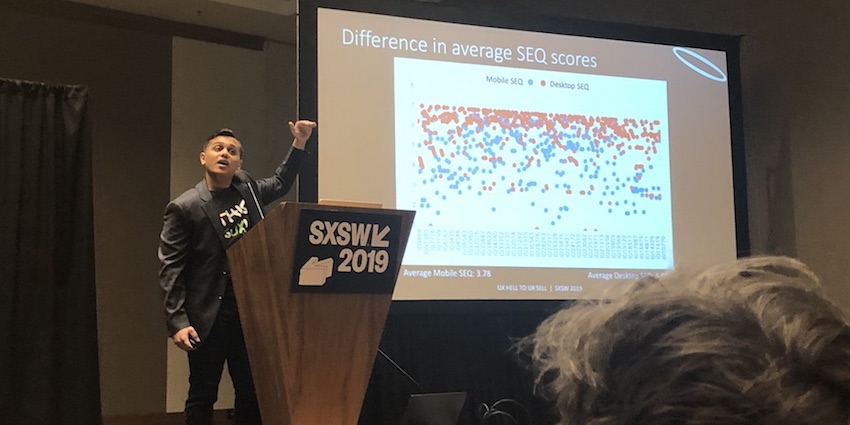

Rit himself presented on the SXSW stage, joining usability analyst Craig Tomlin to discuss findings from a dataset of over 100,000 usability tests. But ideas about UX and user-centric design abounded at the conference, touching many fields and surprising us with the visions they held for the future.

Online courts make justice more accessible

One of the most fascinating talks we attended was Adopting Online Courts in Utah’s Legal System, which showcased an ongoing experiment in Utah aimed at broadening access to justice.

Currently, the speakers explained, around 80% of civil legal needs go unmet in the US. One of the key problems is uneven “access to justice” – many people can’t afford legal counsel, can’t get time off work to come into court, have limited mobility, or they’re just unfamiliar and overwhelmed by the complexities of the legal system.

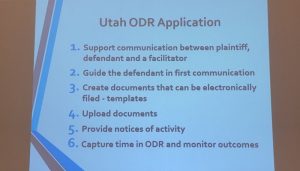

The solution Utah is experimenting with is Online Dispute Resolution (ODR): enabling people to resolve their legal issues online, through asynchronous communication with the other parties and a facilitator.

Utah built their ODR platform from the ground up, starting with use cases and user goals. They had lists of key actions users would need to take, common use cases and flows, and knowledge gaps they expected to have to fill. As the presenters told us, it was “explicitly designed for litigants, not for those representing them.”

Throughout the platform (we saw several screenshots), the word choices smartly avoided “legalese” in favor of plain language that a typical user could easily comprehend.

Visually, the UI was clean, modern, with plenty of white space and not too much going on. And — it was mobile responsive! After all, if the primary problem is access to justice, it’s important to remember that not everyone has easy access to a computer.

For now, “online court” in Utah is limited to small claims cases, the most straightforward and impactful scenario for this type of solution. They’ve already seen a decrease in defaults (that is, a party’s failure to engage in the legal proceedings of their case).

Looking towards the future, the presenters suggested that ODR could have uses in traffic cases, family law, and potentially even low-level misdemeanor cases.

Virtual reality provides in-car entertainment experiences

At the SXSW Mercedes Media Lounge, Rit and I were lucky enough to get a test ride with the brand-new Lucid Dreams in-car VR system.

The experimental program makes use of an Oculus headset, motion-sensor cameras, and data from the car to re-imagine the passenger’s journey in real-time in a virtual world.

The key, their team told us, was making sure that the perceived speed, acceleration, and movement in the virtual setting exactly matched what the passenger’s body felt – or motion sickness could quickly set in.

That’s certainly higher stakes than usual for designing a user-centric experience!

Luckily, the Mercedes team knew what they were doing, and neither of us felt the least bit sick.

As we drove the streets of Austin, an other-planetary world flew by us, featuring alien ruins, laser light shows, and whales and rays that breached from the water skimming underfoot. The scenery was all auto-generated based on the constant stream of GPS and motion data, keeping things fresh and interesting.

As the program and the technology advanced, they explained to us, any virtual world could be created for the passenger to zoom through. Interactive elements could be added: perhaps a virtual Pokemon game, for example, in which you could catch creatures that popped up along the roadside.

Read: The UX of Pokemon Go

With the era of the driverless car approaching, a VR experience like Lucid Dreams offers new horizons for in-car entertainment just as our in-car free time is about to increase.

New urban planning paradigms seek a more inclusive city

At a session called Design Strategies for Truly Inclusive Cities, several leaders involved in urban planning discussed how city design could shift to a more holistic, human-centered approach.

Much of this session focused on collecting input and feedback from community members, incorporating it into development plans, and accommodating and balancing the needs of different community stakeholders.

Architect Ren Yee in particular had an interesting story to tell about a planned community he worked on in Helmond, Netherlands. From the very beginning, community residents were intimately involved in conversations about what the development would look like and what it would contain.

Not only was planning driven by feedback, though, but the construction itself was done iteratively. After zoning the whole community, chunks were built over multiple phases (for example, in the first building phase just a few chunks each of residential and commercial areas were constructed).

In between, managers could observe how the community grew and whether any imbalances were materializing. Then, they could reevaluate and adjust the original plans to designate new zones or prioritize different chunks to be built next.

“The district is never ‘finished,'” read one of Ren’s slides, “but will constantly be adapted to changing circumstances, wishes and technologies.”

As experience becomes a critical differentiator in more and more industries, we’ll only see an increase in the applications of human-centered design thinking and methods. It’s already evident from this year’s SXSW presentations that the future looks human-centric.

We’re just happy to be a part of it.