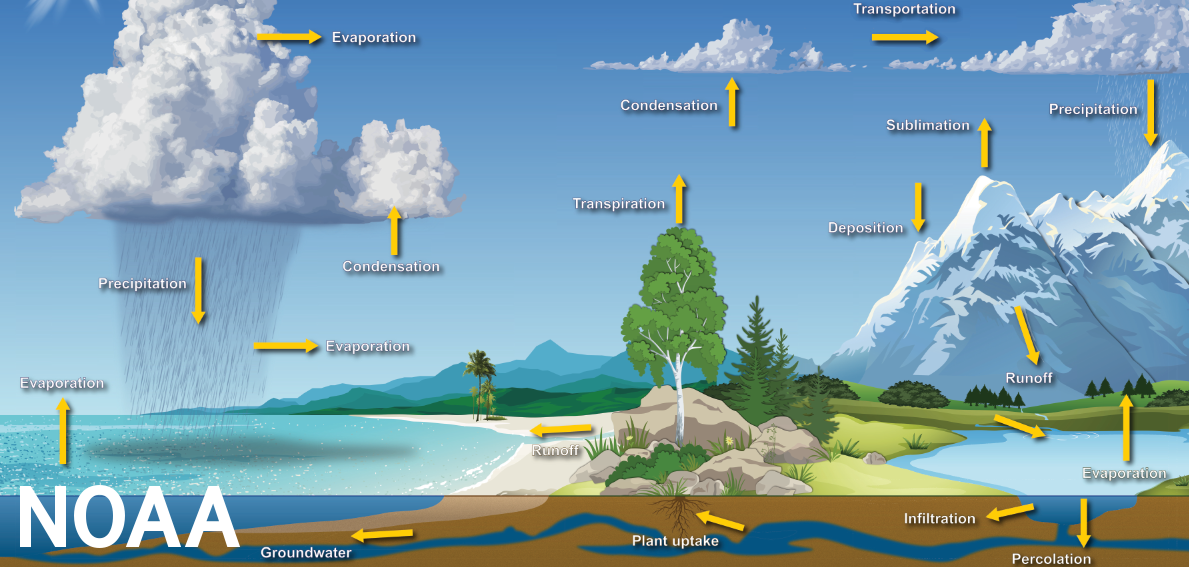

Not unlike water molecules passing from clouds, to rain, to surface water, and back to the clouds above, research data too has a life cycle. Often, it looks something like this:

You do the research and collect your data

↓

You analyze it and figure out what it means

↓

You turn it into a report or presentation

↓

Actions or decisions are taken (or sometimes not taken) based on the findings.

↓

And then, frequently: The report is shelved in a cloud storage folder somewhere and never seen again. Some of the key findings and lessons from the research will live on in the memories of those team members who were involved at the time.

Much like the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Indiana Jones

Don’t get me wrong – those lessons learned will serve the rememberers well. The very act of doing research, and of analyzing, synthesizing, and presenting the findings, builds important muscles: repeatable skills for how to facilitate studies, critically evaluate datasets, recognize patterns, and effectively communicate findings. Exercising these research muscles strengthens your team and makes them more effective in the future.

Read more: Getting started with UX research

Not only that, but as long as you remember the lessons of past research, you can continue to apply those learnings to new decisions and strategies.

But is that it? If so, then the data itself is without value after the initial synthesis and presentation. It provides a one-time injection of insight in order to inform a specific, time-boxed decision; it maintains a smaller, long-tail legacy in the memory and skillset of individual team members; but effectively, the data itself has reached the end of its life cycle.

Old data never dies, it just fades away

When the outcomes of a research exercise live on only in the minds of individual team members, it leads to 2 problems:

- Loss of fidelity: Human memory is imperfect, biased, and limited. As more time passes, the lessons learned become hazier. Details may be misremembered or half-remembered. Bias impacts which insights stick in someone’s memory, and which ones fade away.

- Team turnover: Every team experiences turnover; people come, people go. When a member leaves the team, there is inevitably a loss of institutional knowledge. All the things that person knew and understood – about the product, the customers, the data – goes with them. If they were the only one who retained a certain insight, then that insight is lost to those who remain.

The root of these problems, of course, is not that the data is no longer there to refer back to. Usually, old datasets are still sitting around somewhere. They could be double-checked by an interested person with access. But the fact is, they almost never will be, and for good reasons.

Firstly, the person in need of the information has to know the information even exists, and in which dataset it can be found. Then, they need to locate it – perhaps having to decipher a long-gone team member’s personal organizational system, labeling patterns, and shorthand lingo. If it’s not a case of turnover, they may need to figure out their own organizing and labeling decisions and shorthand from months or years ago.

Read more: Trymata’s new UX research repository

In other words, even if the data is still around, it tends to be difficult to access, and difficult to use. Thus, old data eventually just fades away.

And what that means is: you’re not getting nearly as much out of it as you could.

Solving the data life-cycle problem

What steps can be taken to minimize the loss of value from UX research data? How do research repositories fit into the picture, and what problems do they leave unsolved?

Read the full article on the Trymata CEO’s Linkedin >

How to drive digital growth with Trymata’s Product Analytics