“You X …” is a recurring series on creative ideas and interesting stories to inspire great UX design. You X History is the third in this series.

I’m sure you’ve heard the stories of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs living and working and building their companies out of their parents’ garage, right? Back when Microsoft and Apple were just small teams of individuals with no clout in their industries led and anchored by innovative thinkers poised to disrupt the world of tech forever, yada yada yada. Startup culture before startups were a thing.

But have you ever heard the story of Oda Nobunaga?

If you think the term “disruptive” is just an overused, hollowed-out buzzword in 2019, you’re already late to the bandwagon. In fact, it’s been overplayed since at least June of 1560. That summer, Oda Nobunaga, a brilliant young daimyo (Japanese warlord of a province) led his obscure clan of a couple thousand to a decisive victory over a vastly superior force, establishing himself as the de facto disrupter of status quo.

This is the story of an ambitious dreamer, not unlike those in the startup world today.

The lay of the land of Sengoku Japan

For centuries leading up to Nobunaga’s ambition, Japan had been under the control of a Shogunate, the military rule of the country. In the decades leading up to 1560, the Ashikaga Shogunate had become weak and was at the mercy of a generation of powerful daimyo who challenged the Ashikaga rule.

This period (1467-1600) would be known as the Sengoku (warring states) period and would end with the unification of modern day Japan. Much of Japan’s most widely-known history occurred during the Sengoku period.

Legendary director Akira Kurosawa’s filmography brought this period to life for Western audiences, made easier by the high-drama exploits of daimyos. Nobunaga makes an appearance in Kurosawa’s 1980 Kagemusha, as an ever-present metaphor for the inevitability of change.

A would-be Shogun’s summer in Owari

One particular daimyo, Imagawa Yoshimoto, was especially bright, capable, and commanded a large force of about 25k men. He was so sure of his abilities that he began marching to Kyoto, the then-capital of Japan, to defeat the Ashikaga Shogunate and install himself as Shogun.

But first, Yoshimoto had to pass through Owari, a sparsely populated fishing province led by the Oda clan. Owari suffered from years of family in-fighting and wasn’t remotely considered to be a threat to anyone. Yoshimoto decided to declare war on the province as a sort of victory lap en route to becoming Shogun.

Neither Yoshimoto, nor the Imagawa name, would make it out of Owari alive.

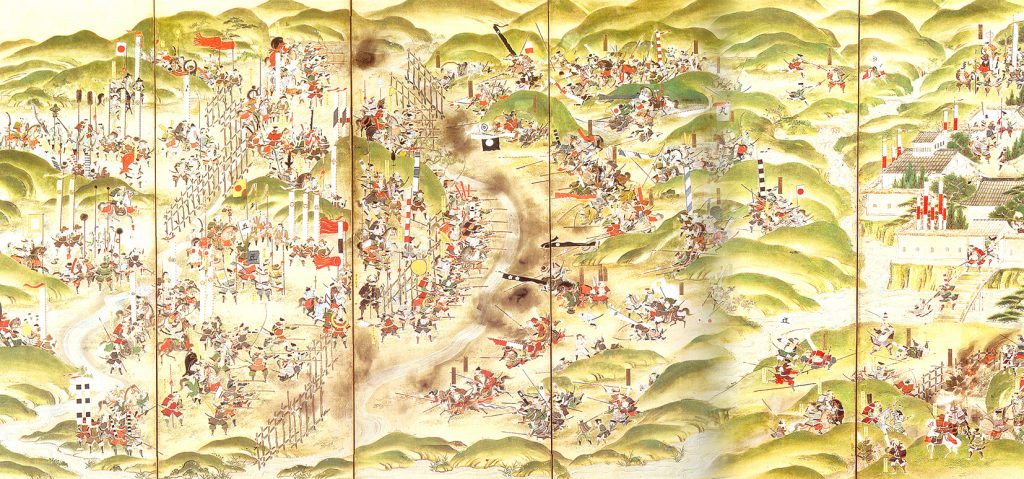

The Battle of Okehazama and the emergence of brilliance

Yoshimoto’s Owari campaign began by conquering two border fortresses with little or no resistance, as expected. He halted his forces to rest in a wooded gorge, allowing his army to celebrate their recent successes as well as their impending success.

The Oda scouts reported Yoshimoto’s movements back to Nobunaga who faced a difficult choice: holdup in their most defensible fortress, or make a frontal assault on the enemy. His advisors suggested the former, while his army’s strength, numbering between 2-3k, made a frontal assault suicidal. Nobunaga knew that being defensive would be to stall the inevitable.

So he invented a third option

Nobunaga created a “dummy” army, composed of banners lined up along the walls of a nearby fortress to Yoshimoto’s resting troops. This created the illusion that the Oda clan would wait for Yoshimoto to attack. Meanwhile, Nobunaga maneuvered his actual army behind Yoshimoto’s position.

On the day of the attack, blessed by a thunderstorm masking the stomp of 3k men bearing down on them, the Imagawa clan was caught completely off-guard. Despite outnumbering the enemy by at least 8:1, the surprise attack coupled with their vulnerable (probably drunken) state caused a near-immediate route of Imagawa troops.

Yoshimoto, hearing the commotion, charged from his tent and ordered his men to settle down, not realizing the samurai he was speaking to were Oda soldiers. He was swiftly beheaded.

Yoshimoto, hearing the commotion, charged from his tent and ordered his men to settle down, not realizing the samurai he was speaking to were Oda soldiers. He was swiftly beheaded.

With their leader dead, the remaining Imagawa troops joined the Oda cause, propelling Nobunaga from total obscurity well into the ranks of the most powerful daimyo alive, all in the span of mere hours.

Capitalizing on momentum by embracing innovation

The shakeup of Okehazama resulted in Nobunaga sieging Kyoto and installing a puppet Shogunate while he focused on conquering the rest of Japan. Although he now had a formidable force and forged key alliances, many of his contemporaries were thought of as being superior not only in strength, but in strategy as well.

While such notable figures as Shingen Takeda and Uesugi Kenshin may have had been more respected for their history of battle prowess, Nobunaga had no intention of playing by their traditionalist rules.

While such notable figures as Shingen Takeda and Uesugi Kenshin may have had been more respected for their history of battle prowess, Nobunaga had no intention of playing by their traditionalist rules.

Instead, Nobunaga would usher in a new modality of warfare in his native land, as well as inventing battle tactics to be utilized by the rest of the world.

Japan had been in contact with the West for decades years before Nobunaga took power. Most of Japan’s elites were disparaging and dismissive of Western goods and knowledge, especially firearms. To many daimyo, the use of firearms was seen as “dishonorable” and never fully utilized them.

Nobunaga, however, saw the potential of firearms immediately.

With rifles, Nobunaga knew that his armies, many of them former fishermen, would standup to the highly trained, well-supplied Japanese noble class of samurai that his rivals so valued.

This break with tradition would prove to be validated in a landmark battle against Shingen Takeda’s son and his fearsome calvary at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575.

Takeda’s world-class calvary, unmatched in their abilities, charged into a near-instantaneous defeat at the barrels of Oda riflemen.

Nobunaga arranged his men into 3 rows, and ordered them to fire in a successive technique that would later become the standard tactical use of firearms in the West, referred to as “volley-fire.” This is the earliest recorded use of this tactic, which would be repeated by the Ottoman Turks and Portuguese decades later, and utilized by the British Empire well-into the 19th century.

With the Takeda clan defeated, and Uesugi Kenshin dying of natural causes, there were no rivals left standing between Nobunaga and a unified Japan.

Murdering the elite and diversifying your team

What made Nobunaga’s continuous victories against his rivals especially disruptive was that his officers were composed almost entirely of peasants.

Under Nobunaga, the elite were slaughtered repeatedly by the poor.

Although meritocracy in 2019 is fraught with unacknowledged privilege, Nobunaga was considered an iconoclast for his merit-based leadership. He sought-out others similar to himself, those who struggled to make a name for themselves due to class, family, or tradition.

His generals, including Toyotomi Hideyoshi who would become the first leader of peaceful and unified Japan, were promoted on performance, abolishing class in his military ranks.

Nobunaga’s greatest friend and ally, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was a shrewd intellectual who echoed Nobunaga’s push towards modernity. Ieyasu would go on to establish the Tokugawa Shogunate, the last Shogunate of Japan.

A patron of the arts, Nobunaga discovered and supported Kanō Eitoku, whose art would usher in an entirely new style (the Kanō school) that would someday influence Western artists such as van Gogh and Klimt.

Azuchi Castle (now destroyed aside from the innovative, earthquake resistant foundation) marked the beginning of the Azuchi-Miramichi period of castle building, resulting in many of Japan’s most beloved structures still standing today.

From Owari to modern Japan, startups, and the afterlife

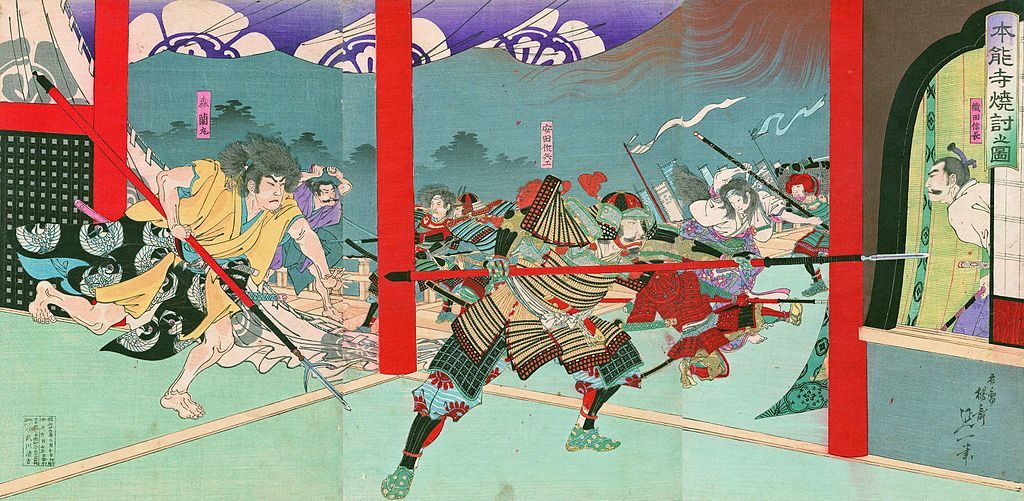

If you’ve read closely, you may have noticed that Toyotomi Hideyoshi, not Nobunaga, was the first ruler of a peacefully unified Japan. And also, that Tokugawa Ieyasu established the last Shogunate in 1600, not Nobunaga. That’s because Oda Nobunaga killed himself as his castle burned to the ground around him after a shock betrayal in 1582.

Unfortunately, at least one of Nobunaga’s generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, was power-hungry and, seizing an opportunity, led his army to Nobunaga, vacationing nearby, totally undefended. Hideyoshi immediately abandoned his campaign to conquer the remaining 1/3 of Japan not under Oda control, and swiftly quelled Mitsuhide’s rebellion. He then adopted Nobunaga’s mission as his own, and the Oda clan followed.

The influence Nobunaga left behind is encapsulated in a Japanese idiom reflecting the unification of modern-day Japan:

Nobunaga pounds the national rice cake, Hideyoshi kneads it, but it is Ieyasu who sits down to eat it.

While Nobunaga did all the heavy-lifting and positioned his successors well, Hideyoshi finished the task and established order, but after an untimely death with no viable heir, it was Ieyasu who finalized and enjoyed a centuries-long golden age in Japan.

So what does the story of Nobunaga, the lord of an obscure province who became one of history’s greatest disruptors, offer startups?

It’s all or nothing all the time

Like in the Battle of Okehazama, startups can’t often wait for success to come to them. The only thing that’s coming down the pipeline is someone much, much bigger. Nobunaga knew waiting for his enemy would be a certain defeat, and so he planned accordingly.

If your startup isn’t willing to do whatever it takes to actually disrupt the status quo, you’re merely waiting for an inevitable defeat.

Related: UX Unleashed: TryMyUI’s unlimited user testing offer

Embrace innovation

Nobunaga’s greatest successes were due not only to ingenuity, but a willingness to break with tradition and embrace modernity. Your industry is most likely lorded over by some Ashikaga Shogunate-like force that is holding true to whatever got them to that position.

What you need is the futuristic fire power they aren’t using.

This could come in many forms: cutting-edge software, new techniques, different customer demographics, contemporary management styles, aggressive marketing strategies, etc. No company is doing everything right, and no established company can see the flaws in themselves that you can.

Take Jeff Bezos, who would come to take on the great retail giants of the 20th century – and win. During Amazon’s formative years, Bezos spent more on UX research than in marketing at a ratio 100:1. This was the late 90s, so if you think UX is a foreign concept to many businesses today, think about UX in 1999!

A startup will not beat industry leaders by following the rules and examples already in place.

Meritocracy is a myth; the best teams are made up of people who want to be there

Obviously, Nobunaga owed a lot of his conquest to his team. Even the general that betrayed him was a great military leader who, at the very least, wasn’t afraid to seize an opportunity.

Nobunaga surrounded himself with people that saw the world the way he saw it, not people who came from any particular region or class. His greatest general and eventual successor, Hideyoshi, grew up as an orphan. His other successor, Ieyasu, was an enemy-turned-ally due to their similar styles in leadership and willingness to break tradition.

Evaluating who works best in a startup situation isn’t just boiling roles down to ROIs or meeting KPIs/KPMs; it’s building a team with a shared sense of purpose and vision, and rewarding and enriching their professional lives.

Really, the only thing Nobunaga did wrong with his startup disruption was putting too much trust in any one person, giving them an army, and then vacationing in a nearby castle. And how often does that even come up? Except that one time?

You may be interested in: